All of my opinions are italicized and sources are in blue.

As reported by Ars Technica,

Researchers have found a malicious backdoor in a compression tool that made its way into widely used Linux distributions, including those from Red Hat and Debian.

The compression utility, known as xz Utils, introduced the malicious code in versions 5.6.0 and 5.6.1, according to Andres Freund, the developer who discovered it. There are no known reports of those versions being incorporated into any production releases for major Linux distributions, but both Red Hat and Debian reported that recently published beta releases used at least one of the backdoored versions—specifically, in Fedora Rawhide and Debian testing, unstable and experimental distributions. A stable release of Arch Linux is also affected. That distribution, however, isn’t used in production systems.

Because the backdoor was discovered before the malicious versions of xz Utils were added to production versions of Linux, “it’s not really affecting anyone in the real world,” Will Dormann, a senior vulnerability analyst at security firm Analygence, said in an online interview. “BUT that’s only because it was discovered early due to bad actor sloppiness. Had it not been discovered, it would have been catastrophic to the world.”

Even though most people don’t use Linux, many large corporations do. In fact, most of the internet is based on Linux. So, you can imagine what would happen if this backdoor made it through.

Several people reported that the multiple apps included in the HomeBrew package manager for macOS rely on the backdoored 5.6.1 version of xz Utils. HomeBrew has now rolled back the utility to version 5.4.6. Maintainers have more details available here.

The first signs of the backdoor were introduced in a February 23 update that added obfuscated code, officials from Red Hat said in an email. An update the following day included a malicious install script that injected itself into functions used by sshd, the binary file that makes SSH work. The malicious code has resided only in the archived releases—known as tarballs—which are released upstream. So-called GIT code available in repositories aren’t affected, although they do contain second-stage artifacts allowing the injection during the build time. In the event the obfuscated code introduced on February 23 is present, the artifacts in the GIT version allow the backdoor to operate.

The malicious changes were submitted by JiaT75, one of the two main xz Utils developers with years of contributions to the project.

“Given the activity over several weeks, the committer is either directly involved or there was some quite severe compromise of their system,” Freund wrote. “Unfortunately the latter looks like the less likely explanation, given they communicated on various lists about the ‘fixes’” provided in recent updates. Those updates and fixes can be found here, here, here, and here.

On Thursday, someone using the developer’s name took to a developer site for Ubuntu to ask that the backdoored version 5.6.1 be incorporated into production versions because it fixed bugs that caused a tool known as Valgrind to malfunction.

“This could break build scripts and test pipelines that expect specific output from Valgrind in order to pass,” the person warned, from an account that was created the same day.

One of maintainers for Fedora said Friday that the same developer approached them in recent weeks to ask that Fedora 40, a beta release, incorporate one of the backdoored utility versions.

“We even worked with him to fix the valgrind issue (which it turns out now was caused by the backdoor he had added),” the Ubuntu maintainer said. “He has been part of the xz project for two years, adding all sorts of binary test files, and with this level of sophistication, we would be suspicious of even older versions of xz until proven otherwise.”

Maintainers for xz Utils didn’t immediately respond to emails asking questions.

The malicious versions, researchers said, intentionally interfere with authentication performed by SSH, a commonly used protocol for connecting remotely to systems. SSH provides robust encryption to ensure that only authorized parties connect to a remote system. The backdoor is designed to allow a malicious actor to break the authentication and, from there, gain unauthorized access to the entire system. The backdoor works by injecting code during a key phase of the login process.

“I have not yet analyzed precisely what is being checked for in the injected code, to allow unauthorized access,” Freund wrote. “Since this is running in a pre-authentication context, it seems likely to allow some form of access or other form of remote code execution.”

In some cases, the backdoor has been unable to work as intended. The build environment on Fedora 40, for example, contains incompatibilities that prevent the injection from correctly occurring. Fedora 40 has now reverted to the 5.4.x versions of xz Utils.

Xz Utils is available for most if not all Linux distributions, but not all of them include it by default. Anyone using Linux should check with their distributor immediately to determine if their system is affected. Freund provided a script for detecting if an SSH system is vulnerable.

As reported by Wired,

If you still hold any notion that Google Chrome’s “Incognito mode” is a good way to protect your privacy online, now’s a good time to stop.

Google has agreed to delete “billions of data records” the company collected while users browsed the web using Incognito mode, according to documents filed in federal court in San Francisco on Monday. The agreement, part of a settlement in a class action lawsuit filed in 2020, caps off years of disclosures about Google’s practices that shed light on how much data the tech giant siphons from its users—even when they’re in private-browsing mode.

Google has agreed to delete “billions of data records” the company collected while users browsed the web using Incognito mode, according to documents filed in federal court in San Francisco on Monday. The agreement, part of a settlement in a class action lawsuit filed in 2020, caps off years of disclosures about Google’s practices that shed light on how much data the tech giant siphons from its users—even when they’re in private-browsing mode.

Under the terms of the settlement, Google must further update the Incognito mode “splash page” that appears anytime you open an Incognito mode Chrome window after previously updating it in January. The Incognito splash page will explicitly state that Google collects data from third-party websites “regardless of which browsing or browser mode you use,” and stipulate that “third-party sites and apps that integrate our services may still share information with Google,” among other changes. Details about Google’s private-browsing data collection must also appear in the company’s privacy policy.

Additionally, some of the data that Google previously collected on Incognito users will be deleted. This includes “private-browsing data” that is “older than nine months” from the date that Google signed the term sheet of the settlement last December, as well as private-browsing data collected throughout December 2023. All told, this amounts to those “billions of data records.” Certain documents in the case referring to Google’s data collection methods remain sealed, however, making it difficult to assess how thorough the deletion process will be.

Google spokesperson Jose Castaneda says in a statement that the company “is happy to delete old technical data that was never associated with an individual and was never used for any form of personalization.” Castaneda also noted that the company will now pay “zero” dollars as part of the settlement after earlier facing a $5 billion penalty.

Other steps Google must take will include continuing to “block third-party cookies within Incognito mode for five years,” partially redacting IP addresses to prevent re-identification of anonymized user data, and removing certain header information that can currently be used to identify users with Incognito mode active.

The data-deletion portion of the settlement agreement follows preemptive changes to Google’s Incognito mode data collection and the ways it describes what Incognito mode does. For nearly four years, Google has been phasing out third-party cookies, which the company says it plans to completely block by the end of 2024. Google also updated Chrome’s Incognito mode “splash page” in January with weaker language to signify that using Incognito is not “private,” but merely “more private” than not using it.

The settlement’s relief is strictly “injunctive,” meaning its central purpose is to put an end to Google activities that the plaintiffs claim are unlawful. The settlement does not rule out any future claims—The Wall Street Journal reports that the plaintiffs’ attorneys had filed at least 50 such lawsuits in California on Monday—though the plaintiffs note that monetary relief in privacy cases is far more difficult to obtain. The important thing, the plaintiffs’ lawyers argue, is effecting changes at Google now that will provide the greatest, immediate benefit to the largest number of users.

Critics of Incognito, a staple of the Chrome browser since 2008, say that, at best, the protections it offers fall flat in the face of the sophisticated commercial surveillance bearing down on most users today; at worst, they say, the feature fills people with a false sense of security, helping companies like Google passively monitor millions of users who’ve been duped into thinking they’re browsing alone.

As reported by The Guardian,

Google is reportedly drawing up plans to charge for AI-enhanced search features, in what would be the biggest shake-up to the company’s revenue model in its history.

The radical shift is a natural consequence of the vast expense required to provide the service, experts say, and would leave every leading player in the sector offering some variety of subscription model to cover its costs.

Google’s proposals, first reported by the Financial Times, would entail the company exclusively offering its new search feature to users of its premium subscription services, which customers already have to sign up to if they want to use artificial intelligence assistants in other Google tools such as Gmail and its office suite.

With that search experience, being trialled in beta for selected users, Google’s generative AI is used to respond to queries directly with a single answer, in a similar style to the conversational approach of ChatGPT and competitors.

“AI search is more expensive to compute than Google’s traditional search processes. So in charging for AI search Google will be seeking to at least recoup these costs,” said Heather Dawe, chief data scientist at the digital transformation consultancy UST.

Much of the focus within AI is on the huge expense of the computing power used to train cutting-edge generative models. In the last year Amazon ran a single training run that cost $65m (£51m), according to James Hamilton, an engineer, who expects, in the near future, the company to break the $1bn mark.

Last week, OpenAI and Microsoft announced plans to build a $100bn datacentre for AI training, while in January Mark Zuckerberg said his goal was to spend at least $9bn just on Nvidia GPUs alone.

But the cost of training AI is just a tenth of the total cost of the sector, according to the analyst Brent Thill at the investment firm Jefferies. Thill wrote in a briefing note: “The majority of AI compute spend today is directed to the running, not training, of models, and 90%+ of AI compute spend today is being directed towards inferencing [the process by which an AI model is queried], as inferencing spend has been growing much faster than training as more models and tools get put into production.”

He added: “Some have priced new Gen AI features at a monthly rate, betting that higher charges will cover usage expenses, while others have priced on a per-usage basis to protect themselves on the cost-side. Some have also incorporated into existing plans, hoping to drive [user] growth.”

Competitors in AI search offer similar subscription plans. Perplexity, an AI-powered search engine, runs no adverts but offers a $20 monthly “pro” tier that provides access to more powerful AI models and unlimited use.

Others, though, continue to offer their products at a loss. The AI features in Microsoft’s Bing are free to use but tied to the company’s Edge browser. The browsing and search startup Arc offers its products free to users and says it intends to raise revenue in future by charging companies for business features.

As reported by Ars Technica,

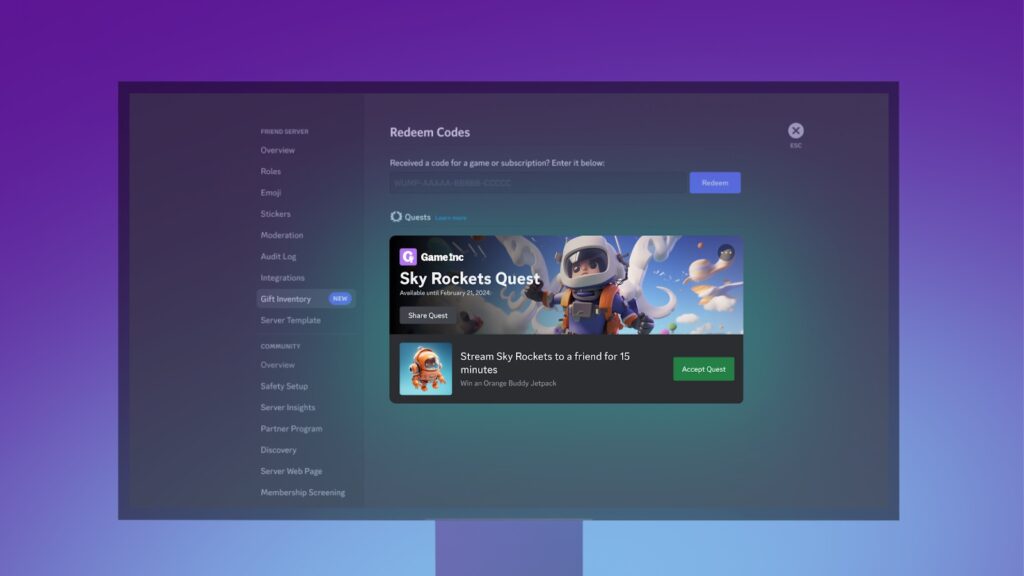

Discord had long been strongly opposed to ads, but starting this week, it’s giving video game makers the ability to advertise to its users. The introduction of so-called Sponsored Quests marks a notable change from the startup’s previous business model, but, at least for now, it seems much less intrusive than the ads shoved into other social media platforms, especially since Discord users can choose not to engage with them.

Discord first announced Sponsored Quests on March 7, with Peter Sellis, Discord’s SVP of product, writing in a blog post that users would start seeing them in the “coming weeks.” Sponsored Quests offer PC gamers in-game rewards for getting friends to watch a stream of them playing through Discord. Discord senior product communications manager Swaleha Carlson confirmed to Ars Technica that Sponsored Quests launch this week.

The goal is for video games to get exposure to more gamers, serving as a form of marketing. On Saturday, The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) reported that it viewed a slide from a slideshow Discord shows to game developers regarding the ads that reads: “We’ll get you in front of players. And those players will get you into their friend groups.”

Sellis told WSJ that Discord will target ads depending on users’ age, geographic location data, and gameplay. The ads will live on the bottom-left of the screen, but users can opt out of personalized promotions for Quests that are based on activity or data shared with Discord, Swaleha Carlson, senior product communications manager at Discord, told Ars Technica.

“Users may still see Quests, however, if they navigate to their Gift Inventory and/or through contextual entry points like a user’s friends’ activity. They’ll also have the option to hide an in-app promotion for a specific Quest or game they’re not interested in,” she said.

“Users may still see Quests, however, if they navigate to their Gift Inventory and/or through contextual entry points like a user’s friends’ activity. They’ll also have the option to hide an in-app promotion for a specific Quest or game they’re not interested in. “

Discord already tested the ads in May with Lucasfilm Games and Epic Games. Discord users were able to receive Star Wars-themed gear in Fortnite for getting a friend to watch them play Fortnite on PC for at least 15 minutes.

Jason Citron, Discord co-founder and CEO, told Bloomberg in March that the company hopes that one day “every game will offer Quests on Discord.”

It may be a nuisance for users to have to disable personalized promotion for Sponsored Quests when they never asked for them, but it should bring long-term users at least some comfort that their data purportedly doesn’t have to contribute to the marketing. However, it’s unclear if Discord may one day change this. The fact that the platform is implementing ads at all is somewhat surprising. Discord named its avoidance of advertising as one of its key differentiators from traditional social media platforms as recently as late January.

Sponsored Quests differs from other types of ads that would more obviously disrupt Discord users’ experiences, such as pop-up ads or ads viewed alongside chat windows.

Beyond Sponsored Quests, Discord, which launched in 2015, previously announced that it would start selling sponsored profile effects and avatar decorations in the Discord Shop. In March, Discord’s Sellis said this would arrive in the “coming weeks.” Discord is also trying to hire more than 12 people to work in ad sales, WSJ said Saturday, citing anonymous “people familiar with [Discord’s] plans.”

In 2021, Discord enjoyed a nearly three-times revenue boost that it attributed to subscription sales for Nitro, which adds features like HD video streaming and up to 500MB uploads. In March, Citron told Bloomberg that Discord has more than 200 million monthly active users and that the company will “probably” go public eventually.

The publication, citing unnamed “people with knowledge of the matter,” also reported that Discord makes over $600 million in annualized revenue. The startup has raised over $1 billion in funding and is reported to have over $700 million in cash. However, the company reportedly isn’t profitable. It also laid off 17 percent of staffers, or 170 workers, in January.

Meanwhile, ads are the top revenue generator for many other social media platforms, such as Reddit, which recently went public.

While Discord’s first real ads endeavor seems like it will have minimal impact on users who aren’t interested in them, it brings the company down a tricky road that it hasn’t previously navigated. A key priority should be ensuring that any form of ads doesn’t disrupt the primary reasons people like using Discord. As it stands, Sponsored Quests might already put off some users.

“I don’t want my friendships to be monetized or productized in any way,” Zack Mohsen, a reported long-time user and computer hardware engineer based in Seattle, told WSJ.

As reported by The Verge,

Roblox asked a federal judge in California to dismiss a suit from two mothers who allege the platform allowed an illegal gambling ring to prey on their children. Instead, the judge has allowed the case to proceed — though some of the claims, including RICO allegations, have been dismissed.

The company argued that the plaintiffs’ claims were barred by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which prevents any “interactive computer service” — in this case, Roblox — from being held liable for third-party content published on its platform. The court, however, held that Section 230 doesn’t apply here because Roblox isn’t being held liable for content published on its platform. It’s being accused of “facilitating transactions between minors and online casinos that enable illegal gambling, and for allegedly failing to take sufficient steps to warn minors and their parents about those casinos.”

In their complaint, Rachelle Colvin and Danielle Sass accused Roblox of facilitating access to and profiting off of “virtual casinos that exist outside the Roblox ecosystem.” To access these casinos, Roblox users — the vast majority of whom, the complaint notes, are children — buy a digital currency called “Robux” through the Roblox website, which they can then use on gambling websites Satozuki, Studs, and RBLXWild. “Throughout this process, Roblox keeps track of all these electronic transfers and has knowledge of each transfer that occurs in its ecosystem,” the complaint says.

Roblox filed a motion to dismiss, effectively arguing that the children didn’t actually lose any money when they bought Robux and used them to gamble. The company compared Robux purchases to “purchasing cinema or amusement park tickets” since the users were paying “for the pleasure of entertainment per se, not for the prospect of economic gain.” This argument didn’t persuade the judge, who noted that movie or amusement park tickets don’t lose their value once they’re purchased.

“Those tickets do have economic value, even if they cannot be exchanged for cash,” the March 26th order, filed in the US District Court for California’s Northern District, reads. “Similarly, when someone purchases Robux on the Roblox platform, they do so because they can exchange Robux for in-game experiences that are of value to them. There is no reason to distinguish the movie or the roller coaster ride in the real world from an in-game experience in the virtual world.”

There’s also the issue of what these in-game experiences entail. Roblox countered by saying the kids got what they bargained for when they used their Robux in online casinos. “But these are children we’re talking about,” the judge wrote. Turning Roblox’s amusement park analogy on its head, the judge wrote that this situation was more akin to “a casino setting up shop outside an amusement park and luring a child away to wager and lose the tickets to an illegal gambling operation—tickets that the casino can then exchange for cash.”